Introduction

Pin is a tool for the instrumentation of programs. It supports the Linux* and Windows* operating systems and executables for the IA-32, Intel(R) 64 and Intel(R) Many Integrated Core architectures.

Pin allows a tool to insert arbitrary code (written in C or C++) in arbitrary places in the executable. The code is added dynamically while the executable is running. This also makes it possible to attach Pin to an already running process.

Pin provides a rich API that abstracts away the underlying instruction set idiosyncracies and allows context information such as register contents to be passed to the injected code as parameters. Pin automatically saves and restores the registers that are overwritten by the injected code so the application continues to work. Limited access to symbol and debug information is available as well.

Pin includes the source code for a large number of example instrumentation tools like basic block profilers, cache simulators, instruction trace generators, etc. It is easy to derive new tools using the examples as a template.

Tutorial Sections

- How to Instrument With Pin

- Examples

- Callbacks

- Modifying Application Instructions

- Instrumenting multi element instruction operands

- Instrumenting AMX instructions

- Instrumenting IFUNC functions in Linux

- The Pin Advanced Debugging Extensions

- Applying a Pintool to an Application

- Tips for Debugging a Pintool

- Logging Messages from a Pintool

- Performance Considerations

- Memory management

- PinTools Information and Restrictions

- Building Tools on windows

- Libraries for Windows

- Libraries for Linux

- Installation

- Building Your Own Tool

- Pin's makefile Infrastructure

- Feedback

- Disclaimer and Legal Information

Reference Sections

How to Instrument with Pin

Table of Contents

- Pin

- Pintools

- Observations

- Instrumentation Granularity

- Managed platforms support

- Symbols

- Floating Point Support in Analysis Routines

- Instrumenting Multi-threaded Applications

- Avoiding Deadlocks in Multi-threaded Applications

Pin

The best way to think about Pin is as a "just in time" (JIT) compiler. The input to this compiler is not bytecode, however, but a regular executable. Pin intercepts the execution of the first instruction of the executable and generates ("compiles") new code for the straight line code sequence starting at this instruction. It then transfers control to the generated sequence. The generated code sequence is almost identical to the original one, but Pin ensures that it regains control when a branch exits the sequence. After regaining control, Pin generates more code for the branch target and continues execution. Pin makes this efficient by keeping all of the generated code in memory so it can be reused and directly branching from one sequence to another.

In JIT mode, the only code ever executed is the generated code. The original code is only used for reference. When generating code, Pin gives the user an opportunity to inject their own code (instrumentation).

Pin instruments all instructions that are actually excuted. It does not matter in what section they reside. Although there are some exceptions for conditional branches, generally speaking, if an instruction is never executed then it will not be instrumented.

Pintools

Conceptually, instrumentation consists of two components:

- A mechanism that decides where and what code is inserted

- The code to execute at insertion points

These two components are instrumentation and analysis code. Both components live in a single executable, a Pintool. Pintools can be thought of as plugins that can modify the code generation process inside Pin.

The Pintool registers instrumentation callback routines with Pin that are called from Pin whenever new code needs to be generated. This instrumentation callback routine represents the instrumentation component. It inspects the code to be generated, investigates its static properties, and decides if and where to inject calls to analysis functions.

The analysis function gathers data about the application. Pin makes sure that the integer and floating point register state is saved and restored as necessary and allow arguments to be passed to the functions.

The Pintool can also register notification callback routines for events such as thread creation or forking. These callbacks are generally used to gather data or tool initialization or clean up.

Observations

Since a Pintool works like a plugin, it must run in the same address space as Pin and the executable to be instrumented. Hence the Pintool has access to all of the executable's data. It also shares file descriptors and other process information with the executable.

Pin and the Pintool control a program starting with the very first instruction. For executables compiled with shared libraries this implies that the execution of the dynamic loader and all shared libraries will be visible to the Pintool.

When writing tools, it is more important to tune the analysis code than the instrumentation code. This is because the instrumentation is executed once, but analysis code is called many times.

Instrumentation Granularity

As described above, Pin's instrumentation is "just in time" (JIT). Instrumentation occurs immediately before a code sequence is executed for the first time. We call this mode of operation trace instrumentation .

Trace instrumentation lets the Pintool inspect and instrument an executable one trace at a time. Traces usually begin at the target of a taken branch and end with an unconditional branch, including calls and returns. Pin guarantees that a trace is only entered at the top, but it may contain multiple exits. If a branch joins the middle of a trace, Pin constructs a new trace that begins with the branch target. Pin breaks the trace into basic blocks, BBLs. A BBL is a single entrance, single exit sequence of instructions. Branches to the middle of a bbl begin a new trace and hence a new BBL. It is often possible to insert a single analysis call for a BBL, instead of one analysis call for every instruction. Reducing the number of analysis calls makes instrumentation more efficient. Trace instrumentation utilizes the TRACE_AddInstrumentFunction API call.

Note, though, that since Pin is discovering the control flow of the program dynamically as it executes, Pin's BBL can be different from the classical definition of a BBL which you will find in a compiler textbook. For instance, consider the code generated for the body of a switch statement like this

It will generate instructions something like this (for the IA-32 architecture)

In terms of classical basic blocks, each addl instruction is in a single instruction basic block. However as the different switch cases are executed, Pin will generate BBLs which contain all four instructions (when the .L7 case is entered), three instructions (when the .L6 case is entered), and so on. This means that counting Pin BBLs is unlikely to give the count you would expect if you thought that Pin BBLs were the same as the basic blocks in the text book. Here, for instance, if the code branches to .L7 you will count one Pin BBL, but there are four classical basic blocks executed.

Pin also breaks BBLs on some other instructions which may be unexpected, for instance cpuid, popf and REP prefixed instructions all end traces and therefore BBLs. Since REP prefixed instructions are treated as implicit loops, if a REP prefixed instruction iterates more than once, iterations after the first will cause a single instruction BBL to be generated, so in this case you would see more basic blocks executed than you might expect.

As a convenience for Pintool writers, Pin also offers an instruction instrumentation mode which lets the tool inspect and instrument an executable a single instruction at a time. This is essentially identical to trace instrumentation where the Pintool writer has been freed from the responsibilty of iterating over the instructions inside a trace. As decribed under trace instrumentation, certain BBLs and the instructions inside of them may be generated (and hence instrumented) multiple times. Instruction instrumentation utilizes the INS_AddInstrumentFunction API call.

Sometimes, however, it can be useful to look at different granularity than a trace. For this purpose Pin offers two additional modes: image and routine instrumentation. These modes are implemented by "caching" instrumentation requests and hence incur a space overhead, these modes are aslo referred to as ahead-of-time instrumentation.

Image instrumentation lets the Pintool inspect and instrument an entire image, IMG: Image Object, when it is first loaded. A Pintool can walk the sections, SEC: Section Object, of the image, the routines, RTN: Routine Object, of a section, and the instructions, INS of a routine. Instrumentation can be inserted so that it is executed before or after a routine is executed, or before or after an instruction is executed. Image instrumentation utilizes the IMG_AddInstrumentFunction API call. Image instrumentation depends on symbol information to determine routine boundaries hence PIN_InitSymbols must be called before PIN_Init.

Routine instrumentation lets the Pintool inspect and instrument an entire routine when the image it is contained in is first loaded. A Pintool can walk the instructions of a routine. There is not enough information available to break the instructions into BBLs. Instrumentation can be inserted so that it is executed before or after a routine is executed, or before or after an instruction is executed. Routine instrumentation is provided as a convenience for Pintool writers, as an alternative to walking the sections and routines of the image during the Image instrumentation, as described in the previous paragraph.

Routine instrumentation utilizes the RTN_AddInstrumentFunction API call. Instrumentation of routine exits does not work reliably in the presence of tail calls or when return instructions cannot reliably be detected.

Note that in both Image and Routine instrumentation, it is not possible to know whether or not a routine will actually be executed (since these instrumentations are done at image load time). It is possible to walk the instructions only of routines that are executed, in the Trace or Instruction instrumentation routines, by identifying instructions that are the start of routines. See the tool Tests/parse_executed_rtns.cpp.

Managed platforms support

Pin supports all executables including the managed binaries. From Pin point of view managed binary is one more kind of a self-modifying program. There is a way to cause Pin to differentiate the just-in-time compiled code (Jitted code) from all other dynamically generated code and associate Jitted code with appropriate managed functions. To get this functionality, the just-in-time compiler (Jitter) of the running managed platform should support Jit Profiling API

The following capabilities are supported:

- RTN_IsDynamic() API is used to indentify dynamically created code. A routine can be marked as dynamically created using Jit Profiling API only.

- A Pintool can instrument Jitted routines using RTN_AddInstrumentFunction API See the examples Managed platforms support for more information.

Following conditions must be satisfied to get the managed platforms support:

-

Set LD_LIBRARY_PATH environment variables to include pinjitprofiling dynamic library and Pin CRT libraries location.

-

Add the knob support_jit_api to the Pin command line as Pintool option:

<Pin executable> <Pin options> -t <Pintool> -support_jit_api <Other Pintool options> -- <Test application> <Test application options>

Symbols

Pin provides access to function names using the symbol object (SYM). Symbol objects only provide information about the function symbols in the application. Information about other types of symbols (e.g. data symbols), must be obtained independently by the tool.

On Windows, you can use dbghelp.dll for this.

Note that using dbghelp.dll in an instrumented process is not safe and can cause dead-locks in some cases. A possible solution is to find symbols using a different non-instrumented process.

On Linux, you can use libdwarf.so that is provided as part of the Pin kit to access DWARF information.

libdwarf

The libdwarf.so library in the Pin kit is based on the open source libdwarf project (https://www.prevanders.net/dwarf.html) and is linked with Pin CRT.

The libdwarf header files are located at ./extras/libdwarf/libdwarf-0.7.0/src/lib/libdwarf under the Pin root directory.

The libdwarf.so libraries are located together with the other Pin libraries at intel64/lib/ and ia32/lib/.

To use the library, add the libdwarf include directory to the pintool include path, and link with libdwarf.so (add -ldwarf to the link command).

The full documentatino of the libdwarf API can be found in the open source libdwarf project page https://www.prevanders.net/libdwarfdoc/index.html

The repository includes examples for how to use the API, for example the dwarfdump application and several examples under dwarfexample.

The Pin kit includes one pintool that uses the libdwarf library - DebugInfo/libdwarf_client.cpp

The Pin kit includes, in addition to the libdwarf.so library, the sources that were used to build it.

The sources are provided at ./extras/libdwarf under the Pin root directory.

The README file includes instructions on how to build the library from those sources.

PIN_InitSymbols must be called to access functions by name. See Symbols for more information.

Floating Point Support in Analysis Routines

Pin takes care of maintaining the application's floating point state accross analysis routines.

IARG_REG_VALUE cannot be used to pass floating point register values as arguments to analysis routines.

Instrumenting Multi-threaded Applications

Instrumenting a multi-threaded program requires that the tool be thread safe - access to global storage must be coordinated with other threads. Pin tries to provide a conventional C++ program environment for tools, but it is not possible to use the standard library interfaces to manage threads in a Pintool. For example, Linux tools cannot use the pthreads library and Windows tools should not use the Win32 API's to manage threads. Instead, Pin provides its own locking and thread management API's, which the Pintool should use. (See LOCK: Locking Primitives and Pin Thread API.)

Pintools do not need to add explicit locking to instrumentation routines because Pin calls these routines while holding an internal lock called the VM lock. However, Pin does execute analysis and replacement functions in parallel, so Pintools may need to add locking to these routines if they access global data.

Pintools on Linux also need to take care when calling standard C or C++ library routines from analysis or replacement functions because the C and C++ libraries linked into Pintools are not thread-safe. Some simple C / C++ routines are safe to call without locking, because their implementations are inherently thread-safe, however, Pin does not attempt to provide a list of safe routines. If you are in doubt, you should add locking around calls to library functions. In particular, the "errno" value is not multi-thread safe, so tools that use this should provide their own locking. Note that these restrictions only exist on the Unix platforms, as the library routines on Windows are thread safe.

Pin provides call-backs when each thread starts and ends (see PIN_AddThreadStartFunction and PIN_AddThreadFiniFunction). These provide a convenient place for a Pintool to allocate and manipulate thread local data and store it on a thread's local storage.

Pin also provides an analysis routine argument (IARG_THREAD_ID), which passes a Pin-specific thread ID for the calling thread. This ID is different from the O/S system thread ID, and is a small number starting at 0, which can be used as an index to an array of thread data or as the locking value to Pin user locks. See the example Instrumenting Threaded Applications for more information.

In addition to the Pin thread ID, the Pin API provides an efficient thread local storage (TLS), with the option to allocate a new TLS key and associate it with a given data destruction function. Any thread of the process can store and retrieve values in its own slot, referenced by the allocated key. The initial value associated with the key in all threads is NULL. See the example Using TLS for more information.

False sharing occurs when multiple threads access different parts of the same cache line and at least one of them is a write. To maintain memory coherency, the computer must copy the memory from one CPU's cache to another, even though data is not truly shared. False sharing can usually be avoided by padding critical data structures to the size of a cache line, or by rearranging the data layout of structures. See the example Using TLS for more information.

Avoiding Deadlocks in Multi-threaded Applications

Since Pin, the tool, and the application may each acquire and release locks, Pintool developers must take care to avoid deadlocks with either the application or Pin. Deadlocks generally occur when two threads acquire the same locks in a different order. For example, thread A acquires lock L1 and then acquires lock L2, while thread B acquires lock L2 and then acquires lock L1. This will lead to a deadlock if thread A holds lock L1 and waits for L2 while thread B holds lock L2 and waits for L1. To avoid such deadlocks, Pin imposes a hierarchy on the order in which locks must be acquired. Pin generally acquires its own internal locks before the tool acquires any lock (e.g. via PIN_GetLock()). Additionally, we assume that the application may acquire locks at the top of this hierarchy (i.e. before Pin acquires its internal locks). The following diagram illustrates the hierarchy:

Application locks -> Pin internal locks -> Tool locks

Pintool developers should design their Pintools such that they never break this lock hierarchy, and they can do so by following these basic guidelines:

- If the tool acquires any locks from within a Pin call-back, it must release those locks before returning from that call-back. Holding a lock across Pin call-backs violates the hierarchy with respect to the Pin internal locks.

- If the tool acquires any locks from within an analysis routine, it must release those locks before returning from the analysis routine. Holding a lock across Pin analysis routines violates the hierarchy with respect to Pin internal locks and other locks used by the instrumented application itself.

- If the tool calls a Pin API from within a Pin call-back or analysis routine, it should not hold any tool locks when calling the API. Some of the Pin APIs use the internal Pin locks so holding a tool lock before invoking these APIs violates the hierarchy with respect to the Pin internal locks.

- If the tool calls a Pin API from within an analysis routine, it may need to acquire the Pin client lock first by calling PIN_LockClient(). This depends on the API, so check the documentation for the specific API for more information. Note that the tool should not hold any other locks when calling PIN_LockClient(), as described in the previous item.

While these guidelines are sufficient in most cases, they may turn out to be too restrictive for certain use-cases. The next set of guidelines explains the conditions in which it is safe to relax the basic guidelines above:

- In JIT mode, the tool may acquire locks from within an analysis routine and not release them, providing it releases these locks before leaving the trace that contains the analysis routine. The tool must expect that the trace may exit "early" if an application instruction raises an exception. Any lock

L, which the tool might hold when the application raises an exception, must obey the following sub-rules:- The tool must establish a call-back that executes when the application raises an exception and this call-back must release lock

Lif it was acquired at the time the exception occurred. Tools can use PIN_AddContextChangeFunction() to establish this call-back. - The tool must not acquire lock

Lfrom within any Pin call-back, to avoid violating the hierarchy with respect to the Pin internal locks.

- The tool must establish a call-back that executes when the application raises an exception and this call-back must release lock

- If the tool calls a Pin API from an analysis routine, it may acquire and hold a lock

Lwhile calling the API providing that:- Lock

Lis not being acquired from any Pin call-back. This avoids the hierarchy violation with respect to the Pin internal locks. - The Pin API being invoked does not cause application code to execute (e.g., PIN_CallApplicationFunction()). This avoids the hierarchy violation with respect to the locks used by the application itself.

- Lock

Examples

Table of Contents

- Building the Example Tools

- Notes for Building Tools for Windows

- Simple Instruction Count (Instruction Instrumentation)

- Instruction Address Trace (Instruction Instrumentation)

- Memory Reference Trace (Instruction Instrumentation)

- Detecting the Loading and Unloading of Images (Image Instrumentation)

- More Efficient Instruction Counting (Trace Instrumentation)

- Procedure Instruction Count (Routine Instrumentation)

- Using PIN_SafeCopy()

- Order of Instrumentation

- Finding the Value of Function Arguments

- Finding Functions By Name on Windows

- Instrumenting Threaded Applications

- Using TLS

- Using the Fast Buffering APIs

- Finding the Static Properties of an Image

- Detaching Pin from the Application

- Replacing a Routine in Probe Mode

- Instrumenting Child Processes

- Instrumenting Before and After Forks

- Managed platforms support

To illustrate how to write Pintools, we present some simple examples. In the web based version of the manual, you can click on a function in the Pin API to see its documentation.

All the examples presented in the manual can be found in the source/tools/ManualExamples directory.

Building the Example Tools

To build all examples in a directory for ia32 architecture:

$ cd source/tools/ManualExamples $ make all TARGET=ia32

To build all examples in a directory for intel64 architecture:

$ cd source/tools/ManualExamples $ make all TARGET=intel64

To build and run a specific example (e.g., inscount0):

$ cd source/tools/ManualExamples $ make inscount0.test TARGET=intel64

To build a specific example without running it (e.g., inscount0):

$ cd source/tools/ManualExamples $ make obj-intel64/inscount0.so TARGET=intel64

The above applies to the Intel(R) 64 architecture. For the IA-32 architecture, use TARGET=ia32 instead.

$ cd source/tools/ManualExamples $ make obj-ia32/inscount0.so TARGET=ia32

Notes for Building Tools for Windows

Since the tools are built using make, be sure to install cygwin make first.

Open the Visual Studio Command Prompt corresponding to your target architecture, i.e. x86 or x64, and follow the steps in the Building the Example Tools section.

Simple Instruction Count (Instruction Instrumentation)

The example below instruments a program to count the total number of instructions executed. It inserts a call to docount before every instruction. When the program exits, it saves the count in the file inscount.out.

Here is how to run it and display its output (note that the file list is the ls output, so it may be different on your machine, similarly the instruction count will depend on the implementation of ls):

$ ../../../pin -t obj-intel64/inscount0.so -- /bin/ls Makefile atrace.o imageload.out itrace proccount Makefile.example imageload inscount0 itrace.o proccount.o atrace imageload.o inscount0.o itrace.out $ cat inscount.out Count 422838 $

The KNOB exhibited in the example below overwrites the default name for the output file. To use this feature, add "-o <file_name>" to the command line. Tool command line options should be inserted between the tool name and the double dash ("--"). For more information on how to add command line options to your tool, please see KNOB: Commandline Option Handling.

$ ../../../pin -t obj-intel64/inscount0.so -o inscount0.log -- /bin/ls

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/inscount0.cpp

Instruction Address Trace (Instruction Instrumentation)

In the previous example, we did not pass any arguments to docount, the analysis procedure. In this example, we show how to pass arguments. When calling an analysis procedure, Pin allows you to pass the instruction pointer, current value of registers, effective address of memory operations, constants, etc. For a complete list, see IARG_TYPE.

With a small change, we can turn the instruction counting example into a Pintool that prints the address of every instruction that is executed. This tool is useful for understanding the control flow of a program for debugging, or in processor design when simulating an instruction cache.

We change the arguments to INS_InsertCall to pass the address of the instruction about to be executed. We replace docount with printip, which prints the instruction address. It writes its output to the file itrace.out.

This is how to run it and look at the output:

$ ../../../pin -t obj-intel64/itrace.so -- /bin/ls Makefile atrace.o imageload.out itrace proccount Makefile.example imageload inscount0 itrace.o proccount.o atrace imageload.o inscount0.o itrace.out $ head itrace.out 0x40001e90 0x40001e91 0x40001ee4 0x40001ee5 0x40001ee7 0x40001ee8 0x40001ee9 0x40001eea 0x40001ef0 0x40001ee0 $

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/itrace.cpp

Memory Reference Trace (Instruction Instrumentation)

The previous example instruments all instructions. Sometimes a tool may only want to instrument a class of instructions, like memory operations or branch instructions. A tool can do this by using the Pin API which includes functions that classify and examine instructions. The basic API is common to all instruction sets and is described here. In addition, there is an instruction set specific API for the IA-32 ISA.

In this example, we show how to do more selective instrumentation by examining the instructions. This tool generates a trace of all memory addresses referenced by a program. This is also useful for debugging and for simulating a data cache in a processor.

We only instrument instructions that read or write memory. We also use INS_InsertPredicatedCall instead of INS_InsertCall to avoid generating references to instructions that are predicated when the predicate is false. On IA-32 and Intel(R) 64 architectures CMOVcc, FCMOVcc and REP prefixed string operations are treated as being predicated. For CMOVcc and FCMOVcc the predicate is the condition test implied by "cc", for REP prefixed string ops it is that the count register is non-zero.

Since the instrumentation functions are only called once and the analysis functions are called every time an instruction is executed, it is much faster to instrument only the memory operations, as compared to the previous instruction trace example that instruments every instruction.

Here is how to run it and the sample output:

$ ../../../pin -t obj-intel64/pinatrace.so -- /bin/ls Makefile atrace.o imageload.o inscount0.o itrace.out Makefile.example atrace.out imageload.out itrace proccount atrace imageload inscount0 itrace.o proccount.o $ head pinatrace.out 0x40001ee0: R 0xbfffe798 0x40001efd: W 0xbfffe7d4 0x40001f09: W 0xbfffe7d8 0x40001f20: W 0xbfffe864 0x40001f20: W 0xbfffe868 0x40001f20: W 0xbfffe86c 0x40001f20: W 0xbfffe870 0x40001f20: W 0xbfffe874 0x40001f20: W 0xbfffe878 0x40001f20: W 0xbfffe87c $

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/pinatrace.cpp

Detecting the Loading and Unloading of Images (Image Instrumentation)

The example below prints a message to a trace file every time and image is loaded or unloaded. It really abuses the image instrumentation mode as the Pintool neither inspects the image nor adds instrumentation code.

If you invoke it on ls, you would see this output:

$ ../../../pin -t obj-intel64/imageload.so -- /bin/ls Makefile atrace.o imageload.o inscount0.o proccount Makefile.example atrace.out imageload.out itrace proccount.o atrace imageload inscount0 itrace.o trace.out $ cat imageload.out Loading /bin/ls Loading /lib/ld-linux.so.2 Loading /lib/libtermcap.so.2 Loading /lib/i686/libc.so.6 Unloading /bin/ls Unloading /lib/ld-linux.so.2 Unloading /lib/libtermcap.so.2 Unloading /lib/i686/libc.so.6 $

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/imageload.cpp

More Efficient Instruction Counting (Trace Instrumentation)

The example Simple Instruction Count (Instruction Instrumentation) computed the number of executed instructions by inserting a call before every instruction. In this example, we make it more efficient by counting the number of instructions in a BBL: Single entrance, single exit sequence of instructions at instrumentation time, and incrementing the counter once per BBL: Single entrance, single exit sequence of instructions, instead of once per instruction.

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/inscount1.cpp

Procedure Instruction Count (Routine Instrumentation)

The example below instruments a program to count the number of times a procedure is called, and the total number of instructions executed in each procedure. When it finishes, it prints a profile to proccount.out

Executing the tool and sample output:

$ ../../../pin -t obj-intel64/proccount.so -- /bin/grep proccount.cpp Makefile

proccount_SOURCES = proccount.cpp

$ head proccount.out

Procedure Image Address Calls Instructions

_fini libc.so.6 0x40144d00 1 21

__deregister_frame_info libc.so.6 0x40143f60 2 70

__register_frame_info libc.so.6 0x40143df0 2 62

fde_merge libc.so.6 0x40143870 0 8

__init_misc libc.so.6 0x40115824 1 85

__getclktck libc.so.6 0x401157f4 0 2

munmap libc.so.6 0x40112ca0 1 9

mmap libc.so.6 0x40112bb0 1 23

getpagesize libc.so.6 0x4010f934 2 26

$

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/proccount.cpp

Using PIN_SafeCopy()

PIN_SafeCopy is used to copy the specified number of bytes from a source memory region to a destination memory region. This function guarantees safe return to the caller even if the source or destination regions are inaccessible (entirely or partially).

Use of this function also guarantees that the tool reads or writes the values used by the application. For example, on Windows, Pin replaces certain TEB fields when running a tool's analysis code. If the tool accessed these fields directly, it would see the modified values rather than the original ones. Using PIN_SafeCopy() allows the tool to read or write the application's values for these fields.

We recommend using this API any time a tool reads or writes application memory.

$ ../../../pin -t obj-ia32/safecopy.so -- /bin/cp makefile obj-ia32/safecopy.so.makefile.copy $ head safecopy.out Emulate loading from addr 0xbff0057c to ebx Emulate loading from addr 0x64ffd4 to eax Emulate loading from addr 0xbff00598 to esi Emulate loading from addr 0x6501c8 to edi Emulate loading from addr 0x64ff14 to edx Emulate loading from addr 0x64ff1c to edx Emulate loading from addr 0x64ff24 to edx Emulate loading from addr 0x64ff2c to edx Emulate loading from addr 0x64ff34 to edx Emulate loading from addr 0x64ff3c to edx

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/safecopy.cpp.

Order of Instrumentation

Pin provides tools with multiple ways to control the exection order of analysis calls. The exection order depends mainly on the insertion action (IPOINT) and call order (CALL_ORDER). The example below illustrates this behavior by instrumenting all return instructions in three different ways. Additional examples can be found in source/tools/InstrumentationOrderAndVersion.

$ ../../../pin -t obj-ia32/invocation.so -- obj-ia32/little_malloc $ head invocation.out After: IP = 0x64bc5e Before: IP = 0x64bc5e Taken: IP = 0x63a12e After: IP = 0x64bc5e Before: IP = 0x64bc5e Taken: IP = 0x641c76 After: IP = 0x641ca6 After: IP = 0x64bc5e Before: IP = 0x64bc5e Taken: IP = 0x648b02

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/invocation.cpp.

Finding the Value of Function Arguments

Often one needs the know the value of the argument passed into a function, or the return value. You can use Pin to find this information. Using the RTN_InsertCall() function, you can specify the arguments of interest.

The example below prints the input argument for malloc() and free(), and the return value from malloc().

$ ../../../pin -t obj-ia32/malloctrace.so -- /bin/cp makefile obj-ia32/malloctrace.so.makefile.copy $ head malloctrace.out malloc(0x24d) returns 0x6504f8 malloc(0x57) returns 0x650748 malloc(0xc) returns 0x6507a0 malloc(0x3c0) returns 0x6507b0 malloc(0xc) returns 0x650b70

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/malloctrace.cpp.

Finding Functions By Name on Windows

Finding functions by name on Windows requires a different methodology. Several symbols could resolve to the same function address. It is important to check all symbol names.

The following example finds the function name in the symbol table, and uses the symbol address to find the appropriate RTN.

$ ..\..\..\pin -t obj-ia32\w_malloctrace.dll -- ..\Tests\obj-ia32\cp-pin.exe makefile w_malloctrace.makefile.copy $ head *.out Before: RtlAllocateHeap(00150000, 0, 0x94) After: RtlAllocateHeap returns 0x153440 After: RtlAllocateHeap returns 0x153440 Before: RtlAllocateHeap(00150000, 0, 0x20) After: RtlAllocateHeap returns 0 After: RtlAllocateHeap returns 0x1567c0 Before: RtlAllocateHeap(019E0000, 0x8, 0x1800) After: RtlAllocateHeap returns 0x19e0688 Before: RtlAllocateHeap(00150000, 0, 0x1a)thread begin 0 After: RtlAllocateHeap returns 0

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/w_malloctrace.cpp.

Instrumenting Threaded Applications

The following example demonstrates using the ThreadStart() and ThreadFini() notification callbacks. Although ThreadStart() and ThreadFini() are executed under the VM and client locks, they could still contend with resources that are shared by other analysis routines. Using PIN_GetLock() prevents this.

Note that there is known isolation issue when using Pin on Windows. On Windows, a deadlock can occur if a tool opens a file in a callback when run on a multi-threaded application. To work around this problem, open one file in main, and tag the data with the thread ID. See source/tools/ManualExamples/buffer_windows.cpp as an example. This problem does not exist on Linux.

$ ../../../pin -t obj-ia32/malloc_mt.so -- obj-ia32/thread_lin $ head malloc_mt.out thread begin 0 thread 0 entered malloc(24d) thread 0 entered malloc(57) thread 0 entered malloc(c) thread 0 entered malloc(3c0) thread 0 entered malloc(c) thread 0 entered malloc(58) thread 0 entered malloc(56) thread 0 entered malloc(19) thread 0 entered malloc(25c)

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/malloc_mt.cpp

Using TLS

Pin provides efficient thread local storage (TLS) APIs. These APIs allow a tool to create thread-specific data. The example below demonstrates how to use these APIs.

$ ../../../pin -t obj-ia32/inscount_tls.so -- obj-ia32/thread_lin $ head Count[0]= 237993 Count[1]= 213296 Count[2]= 209223 Count[3]= 209223 Count[4]= 209223 Count[5]= 209223 Count[6]= 209223 Count[7]= 209223 Count[8]= 209223 Count[9]= 209223

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/inscount_tls.cpp

Using the Fast Buffering APIs

Pin provides support for buffering data for processing. If all that your analysis callback does is to store its arguments into a buffer, then you should be able to use the buffering API instead, with some performance benefit. PIN_DefineTraceBuffer() defines the buffer that will be used. The buffer is allocated by each thread when it starts up, and deallocated when the thread exits. INS_InsertFillBuffer() writes the requested data directly to the given buffer. The callback delineated in the PIN_DefineTraceBuffer() call is used to process the buffer when the buffer is nearly full, and when the thread exits. Pin does not serialize the calls to this callback, so it is the tool writers responsibilty to make sure this function is thread safe. This example records the PC of all instructions that access memory, and the effective address accessed by the instruction. Note that IARG_REG_REFERENCE, IARG_REG_CONST_REFERENCE, IARG_CONTEXT, IARG_CONST_CONTEXT and IARG_PARTIAL_CONTEXT can NOT be used in the Fast Buffering APIs

$ ../../../pin -t obj-ia32/buffer_linux.so -- obj-ia32/thread_lin $ tail buffer.out.*.* 3263df 330108 3263df 330108 3263f1 a92f43fc 3263f7 a92f4d7d 326404 a92f43fc 32640a a92f4bf8 32640a a92f4bf8 32640f a92f4d94 32641b a92f43fc 326421 a92f4bf8

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/buffer_linux.cpp. This example is appropriate for Linux tools. If you are writing a tool for Windows, please see source/tools/ManualExamples/buffer_windows.cpp

Finding the Static Properties of an Image

It is also possible to use Pin to examine binaries without instrumenting them. This is useful when you need to know static properties of an image. The sample tool below counts the number of instructions in an image, but does not insert any instrumentation.

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/staticcount.cpp

Detaching Pin from the Application

Pin can relinquish control of application any time when invoked via PIN_Detach. Control is returned to the original uninstrumented code and the application runs at native speed. Thereafter no instrumented code is ever executed.

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/detach.cpp

Replacing a Routine in Probe Mode

Probe mode is a method of using Pin to insert probes at the start of specified routines. A probe is a jump instruction that is placed at the start of the specified routine. The probe redirects the flow of control to the replacement function. Before the probe is inserted, the first few instructions of the specified routine are relocated. It is not uncommon for the replacement function to call the replaced routine. Pin provides the relocated address to facilitate this. See the example below.

In probe mode, the application and the replacement routine are run natively. This improves performance, but it puts more responsibility on the tool writer. Probes can only be placed on RTN boundaries.

Many of the PIN APIs that are available in JIT mode are not applicable in Probe mode. In particular, the Pin thread APIs are not supported in Probe mode, because Pin has no information about the threads when the application is run natively. For more information, check the RTN API documentation.

The tool writer must guarantee that there is no jump target where the probe is placed. A probe may be up to 14 bytes long.

Also, it is the tool writer's responsibility to ensure that no thread is currently executing the code where a probe is inserted. Tool writers are encouraged to insert probes when an image is loaded to avoid this problem. Pin will automatically remove the probes when an image is unloaded.

When using probes, Pin must be started with the PIN_StartProgramProbed() API.

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/replacesigprobed.cpp. To build this test, execute:

$ make replacesigprobed.test

Instrumenting Child Processes

The PIN_AddFollowChildProcessFunction() allows you to define the function you will like to execute before an execv'd process starts. Use the -follow_execv option on the command line to instrument the child processes, like this:

$ ../../../pin -follow_execv -t obj-intel64/follow_child_tool.so -- obj-intel64/follow_child_app1 obj-intel64/follow_child_app2

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/follow_child_tool.cpp. To build this test, execute:

$ make follow_child_tool.test

Instrumenting Before and After Forks

Pin allows Pintools to register for notification callbacks around forks. The PIN_AddForkFunction() and PIN_AddForkFunctionProbed() callbacks allow you to define the function you want to execute at one of these FPOINTs:

FPOINT_BEFORE Call-back in parent, just before fork.

FPOINT_AFTER_IN_PARENT Call-back in parent, immediately after fork.

FPOINT_AFTER_IN_CHILD Call-back in child, immediately after fork.

Note that PIN_AddForkFunction() is used for JIT mode and PIN_AddForkFunctionProbed() is used for Probed mode. If the fork() fails, the FPOINT_AFTER_IN_PARENT callback, if it is defined, will execute anyway.

The example can be found in source/tools/ManualExamples/fork_jit_tool.cpp. To build this test, execute:

$ make fork_jit_tool.test

Managed platforms support

Pin allows Pintools to indentify dynamically created code using RTN_IsDynamic() API (only code of functions which are reported by Jit Profiling API). The following example demonstrates use of RTN_IsDynamic() API. This example instruments a program to count the total number of instructions discovered and executed. The instructions are divided to three categories: native instructions, dynamic instructions and instructions without any known routine.

Here is how to run it and display its output with a 32 bit OpenCL sample on Windows:

$ set CL_CONFIG_USE_VTUNE=True $ set INTEL_JIT_PROFILER32=ia32\bin\pinjitprofiling.dll $ ia32\bin\pin.exe -t source\tools\JitProfilingApiTests\obj-ia32\DynamicInsCount.dll -support_jit_api -o DynamicInsCount.out -- ..\OpenCL\Win32\Debug\BitonicSort.exe No command line arguments specified, using default values. Initializing OpenCL runtime... Trying to run on a CPU OpenCL data alignment is 128 bytes. Reading file 'BitonicSort.cl' (size 3435 bytes) Sort order is ascending Input size is 1048576 items Executing OpenCL kernel... Executing reference... Performing verification... Verification succeeded. NDRange perf. counter time 12994.272962 ms. Releasing resources... $ type JitInsCount.out =============================================== Number of executed native instructions: 7631596649 Number of executed jitted instructions: 438983207 Number of executed instructions without any known routine: 12246 =============================================== Number of discovered native instructions: 870531 Number of discovered jitted instructions: 223 Number of discovered instructions without any known routine: 36 =============================================== $

The example can be found in source\tools\JitProfilingApiTests\DynamicInsCount.cpp

Pin allows Pintools to instrument just compiled functions using RTN_AddInstrumentFunction API. Following example instruments a program to log Jitting and running of dynamic functions which are reported by Jit Profiling API.

Here is how to run it with a 64 bit OpenCL sample on Linux:

$ setenv CL_CONFIG_USE_VTUNE True $ setenv INTEL_JIT_PROFILER64 intel64/lib/libpinjitprofiling.so $ ./pin -t source/tools/JitProfilingApiTests/obj-intel64/DynamicFuncInstrument.so -support_jit_api -o DynamicFuncInstrument.out -- ..\OpenCL\Win32\Debug\BitonicSort.exe No command line arguments specified, using default values. Initializing OpenCL runtime... Trying to run on a CPU OpenCL data alignment is 128 bytes. Reading file 'BitonicSort.cl' (size 3435 bytes) Sort order is ascending Input size is 1048576 items Executing OpenCL kernel... Executing reference... Performing verification... Verification succeeded. NDRange perf. counter time 12994.272962 ms. Releasing resources... $

The example can be found in source\tools\JitProfilingApiTests\DynamicFuncInstrument.cpp

Callbacks

The examples in the previous section have introduced a number of ways to register callback functions via the Pin API, such as:

- INS_AddInstrumentFunction (INSCALLBACK fun, VOID *val)

- TRACE_AddInstrumentFunction (TRACECALLBACK fun, VOID *val)

- RTN_AddInstrumentFunction (RTNCALLBACK fun, VOID *val)

- IMG_AddInstrumentFunction (IMGCALLBACK fun, VOID *val)

- PIN_AddFiniFunction (FINICALLBACK fun, VOID *val)

- PIN_AddDetachFunction (DETACHCALLBACK fun, VOID *val)

The extra parameter val (shared by all the registration functions) will be passed to fun as its second argument whenever it is "called back". This is a standard mechanism used in GUI programming with callbacks.

If this feature is not needed, it is safe to pass 0 for val when registering a callback. The expected use of val is to pass a pointer to an instance of a class. Since val is a generic pointer, fun must cast it back to an object before dereferencing the pointer.

Note that all callback registration functions return a PIN_CALLBACK object which can later be used to manipulate the properties of the registered callback (for example change the order in which PIN executes callback functions of the same type). This can be done by calling API functions that manipulates the PIN_CALLBACK object (see PIN callbacks)

Modifying Application Instructions

Although Pin is most commonly used for instrumenting applications, it is also possible to change the application's instructions. The simplest way to do this is to insert an analysis routine to emulate an instruction, and then use INS_Delete() to remove the original instruction. It is also possible to insert direct or indirect branches (using INS_InsertDirectJump and INS_InsertIndirectJump), which makes it easier to emulate instructions that change the control flow.

The memory addresses accessed by an instruction can be modified to refer to a value calculated by an analysis routine using INS_RewriteMemoryOperand.

For instructions whose memory operand has scattered access (vscatter/vgather), use INS_RewriteScatteredMemoryOperand.

Note that in all of the cases where an instruction is modified, the modification is only made after all of the instrumentation routines have been executed. Therefore all of the instrumentation routines see the original, un-modified instruction.

Instrumenting multi element instruction operands

Multi Element operands are operands of vector instructions and tile instructions, where the operand is a vector/matrix of elements and the instruction operation is performed on each element separately. For example, instructions from the SSE, AVX, AVX2, AVX512, AMX extensions, etc.

Pin supports the inspection and instrumentation of the operand elements.

For examples specific to AMX see Instrumenting AMX instructions

The following functions allow inspecting the static attributes of multi element operands:

INS_OperandElementSize

INS_OperandElementCount

INS_MemoryOperandElementSize

INS_MemoryOperandElementCount

INS_OperandHasElements

The following IARGs and interfaces allow inspecting static and runtime attributes of multi element operands:

IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND

IMULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND

The code below demonstrates how to instrument memory operands and pass the effective address of the operand or operand elements to the analysis routine.

When to use IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND

The IMULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND interface is applicable for all the vector instructions which operands have elements.

Some of the operand attributes covered by IMULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND are known at instrumentation time, for example the number of elements and the size of an element.

The attributes that are only known during runtime are the effective addresses and mask values.

For some usages, IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND has alternatives which are discussed in sub-sections below.

Note that typically IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND would be slower than those alternatives.

Reading effective addresses

For reading effective addresses, IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND is recommended for instruction where the memory operand addresses non-contiogous memory

(where INS_HasScatteredMemoryAccess returns TRUE), for example vscatter/vgather.

The other option is calculating the addresses manually by passing the value of the index register, base, scale, etc.

For other vector instruction that don't fall into that category, the alternative to using IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND would be using IARG_MEMORYOP_EA and read the elements manually.

The code below demonstrates how to read effective addresses both ways.

Reading mask values

For reading mask values, an alternative to IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND would be using IARG_REG_CONST_REFERENCE and extract the mask values manually.

When extracted manually, the pintool must know where the mask bit is located in the mask register.

The code below demonstrates how to read mask values both ways.

Instrumenting AMX instructions

This section describes how to read the AMX state, tile configuration and how to instrument the AMX instruction operands, either Memory or TMM registers.

PIN_IsAmxActive returns the current AMX state.

Since instrumentation and analysis happen on different phases in the application flow, it is necessary to check the current AMX state in the analysis routine before analyzing the rest of the data in order to know whether this data is valid or not.

The following functions allow inspecting the dimensions of the matrix:

TileCfg_GetTileBytesPerRow

TileCfg_GetTileRows

These functions get a virtual register that reflects the tiles configuration ( REG_TILECONFIG ) and a TMM register for which the dimensions should be retrieved.

In order to use these functions in an analysis routine we must first inspect the instruction operands to identify the relevant TMM register, as shown in the example below.

AMX and Multi Elements

AMX tiles are multi element operands.

The difference between AMX tile operands and non-AMX multi element operands is that the number of elements is not known until after the LDTILECFG instruction executes, while for the non-AMX operands the number of elements is a static attribute of the instruction.

This means that APIs such as INS_OperandElementCount or INS_MemoryOperandElementCount will return 0 for AMX operands.

Reading a Memory tile content at analysis time requires using IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND that provides the IMULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND interface through which the matrix cells addresses can be retrieved.

Reading a TMM register content at analysis time requires using both IARG_REG_REFERENCE / IARG_REG_CONST_REFERENCE that provide the full content of the tile,

and IARG_MULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND that provides the IMULTI_ELEMENT_OPERAND interface through which the cells offsets within the tile can be retrieved.

Below is code example for the instrumentation callback where we configure the instrumentation.

In this example we instrument TILELOADD and TILESTORED and create an instrumentation that will allow us to read the runtime values of the memory matrix and the tile register matrix.

Below is code example for the analysis routine where we analyze the runtime values of the operands previously configured. In this example we print the cell values of the memory matrix and the tile register matrix.

Instrumenting IFUNC functions in Linux

GNU indirect function (IFUNC) is a feature that allows a developer to create multiple implementations of a given function and to select amongst them at runtime using a resolver function. It is mainly used in glibc. (e.g. memcpy/memset/strcpy)

Pin supports instrumentation on both IFUNC-resolver functions and their implementation/actual function.

Note: instrumentation on the ifunc function is the same as instrumentation on the resolver function and vice versa (since ifunc symbol value is the address of the resolver).

In order to instrument IFUNC function, PIN_InitSymbolsAlt(IFUNC_SYMBOLS) must be called in Pintool main function. Otherwise, IFUNC functions will not be visible in Pintool, only implementation functions (e.g. for memcmp: __memcmp_sse2, __memcmp_ssse3,... )

Usages in Pintool:

- To check if a given rtn is an ifunc function use: Bool isResolver = SYM_IFuncResolver(RTN_Sym(rtn));

- To get the implementation/actual function use: RTN impl = RTN_IFuncImplementation(rtn);

See first example below demonstrating this usage. - RTN_FindByName() returns the implementation/actual function when IFUNC function name is passed as an argument.

To get the resolver use: RTN resolver = RTN_IFuncResolver(rtn), where rtn is the implementation/actual function.

See second example below demonstrating this usage.

The following example demonstrates instrumenting both IFUNC implementation and resolver using RTN_Name(), SYM_IFuncResolver() and RTN_IFuncImplementation():

The following example demonstrates instrumenting both IFUNC implementation and resolver using RTN_FindByName():

The Pin Advanced Debugging Extensions

Pin's advanced debugging extensions allow you to debug an application, even while it runs under Pin in JIT mode. Moreover, your Pintool can add support for new debugger commands, without making any changes to GDB, LLDB or Visual Studio. This allows you to interactively control your Pintool from within a live debugger session. Finally, Pintools can add powerful new debugger features that are enabled via instrumentation. For example, a Pintool can use instrumentation to look for an interesting condition (like a memory buffer overwrite) and then stop at a live debugger session when that condition occurs.

This section illustrates these three concepts:

- Enabling all the traditional debugger features even while running an application under Pin in JIT mode.

- Recognizing new debugger commands in your Pintool to allow interactive control of the tool from a live debugger session.

- Adding support for new debugger features by writing a Pintool.

These features are available on Linux (using GDB) and Windows (using Visual Studio). The Pin APIs are the same in all cases, but their usage from within the debugger may differ because each debugger has a different UI. The following tutorial is divided into two sections: one that is Linux centric and another that is Windows centric. They both describe the same example, so you can continue by reading either section.

Finally, note that these advanced debugging extensions are not at all related to debugging your Pintool. If you have a bug in your tool and need to debug it, see the section Tips for Debugging a Pintool instead.

Advanced Debugging Extensions on Linux

Pin's debugging extensions on Linux work with nearly all modern versions of GDB/LLDB, so you can probably use whatever version of GDB/LLDB is already installed on your system. Pin uses GDB's remote debugger features, so it should work with any version of GDB/LLDB that supports that feature (Yes, LLDB support GDB's remote debugger features).

Throughout this section, we demonstrate the debugging extensions in Pin with the example tool "stack-debugger.cpp", which is available in the directory "source/tools/ManualExamples". You may want to compile that tool and follow along:

$ cd source/tools/ManualExamples $ make DEBUG=1 stack-debugger.test

The tool and its associated test application, "fibonacci", are built in a directory named "obj-ia32", "obj-intel64", etc., depending on your machine type.

To enable the debugging extensions, run Pin with the -appdebug command line switch. This causes Pin to start the application and stop immediately before the first instruction. Pin then prints a message telling you to start debugger.

Linux:

$ ../../../pin -appdebug -t obj-intel64/stack-debugger.so -- obj-intel64/fibonacci.exe 1000 Application stopped until continued from debugger. Start GDB, then issue this command at the prompt: target remote :33030

In another window, start the debugger and enter the command that Pin printed:

Linux:

$ gdb fibonacci (gdb) target remote :33030

At this point, the debugger is attached to the application that is running under Pin. You can set breakpoints, continue execution, print out variables, disassemble code, etc.

Linux:

(gdb) break main Breakpoint 1 at 0x401194: file fibonacci.cpp, line 12. (gdb) cont Continuing. Breakpoint 1, main (argc=2, argv=0x7fbffff3c8) at fibonacci.cpp:12 12 if (argc > 2) (gdb) print argc $1 = 2 (gdb) x/4i $pc 0x401194 <main+27>: cmpl $0x2,0xfffffffffffffe5c(%rbp) 0x40119b <main+34>: je 0x4011c8 <main+79> 0x40119d <main+36>: mov $0x402080,%esi 0x4011a2 <main+41>: mov $0x603300,%edi

Of course, any information you observe in the debugger shows the application's "pure" state. The details of Pin and the tool's instrumentation are hidden. For example, the disassembly you see above shows only the application's instructions, not any of the instructions inserted by the tool. However, when you use commands like "cont" or "step" to advance execution of the application, your tool's instrumentation runs as it normally would under Pin.

- Note

- After connecting the debugger, you should NOT use the "run" command. The application is already running and stopped at the first instruction. Instead, use the "cont" command to continue execution.

Adding New Debugger Commands

The previous section illustrated how you can enable the normal debugger features while running an application under Pin. Now, let's see how your Pintool can add new custom debugger commands, even without changing the debugger itself. Custom debugger commands are useful because they allow you to control your Pintool interactively from within a live debugger session. For example, you can ask your Pintool to print out information that it has collected, or you can interactively enable instrumentation only for certain phases of the application.

To illustrate, see the call to PIN_AddDebugInterpreter() in the stack-debugger tool. That API sets up the following call-back function:

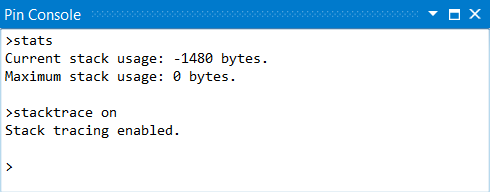

The PIN_AddDebugInterpreter() API allows a Pintool to establish a handler for extended debugger commands. For example, the code snippet above implements the new commands "stats" and "stacktrace on". You can execute these commands in the debugger by using the "monitor" command:

Linux:

(gdb) monitor stats Current stack usage: 688 bytes. Maximum stack usage: 0 bytes.

A Pintool can do various things when the user types an extended debugger command. For example, the "stats" command prints out some information that the tool has collected. Any text that the tool writes to the "result" parameter is printed to the debugger console. Note that the CONTEXT parameter has the register state for the debugger's "focus" thread, so the tool can easily display information about this focus thread.

You can also use an extended debugger command to interactively enable or disable instrumentation in your Pintool, as demonstrated by the "stacktrace on" command. For example, if you wanted to quickly run your Pintool over the application's initial start-up phase, you could run with your Pintool's instrumentation disabled until a breakpoint is triggered. Then, you could use an extended command to enable instrumentation only during the interesting part of the application. In the stack-debugger example above, the call to PIN_RemoveInstrumentation() causes Pin to discard any previous instrumentation, so the tool re-instruments the code when the debugger continues execution of the application. As we will see later, the tool's global variable "EnableInstrumentation" adjusts the instrumentation that it inserts.

Semantic Breakpoints

The last major feature of the advanced debugging extensions is the ability to stop execution at a breakpoint by calling an API from your tool's analysis code. This may sound simple, but it is very powerful. Your Pintool can use instrumentation to look for a complex condition and then stop at a breakpoint when that condition occurs.

The "stack-debugger" tool illustrates this by using instrumentation to observe all the instructions that allocate stack space, and then it stops at a breakpoint whenever the application's stack usage reaches some threshold. In effect, this adds a new feature to the debugger that could not be practically implemented using traditional debugger technology because a traditional debugger can not reasonably find all the instructions that allocate stack space. A Pintool, however, can do this quite easily via instrumentation.

The example code below from the "stack-debugger" tool uses Pin instrumentation to identify all the instructions that allocate stack space.

The call to INS_RegWContain() tests whether an instruction modifies the stack pointer. If it does, we insert an analysis call immediately after the instruction, which checks to see if the application's stack usage exceeds a threshold.

Also notice that all the instrumentation is gated by the global flag "EnableInstrumentation", which we saw earlier in the "stacktrace on" command. Thus, the user can disable instrumentation (with "stacktrace off") in order to execute quickly through uninteresting parts of the application, and then re-enable it (with "stacktrace on") for the interesting parts.

The analysis routine OnStackChangeIf() returns TRUE if the application's stack usage has exceeded the threshold. When this happens, the tool calls the DoBreakpoint() analysis routine, which will stop at the debugger breakpoint. Notice that we use if / then instrumentation here because the call to DoBreakpoint() requires a "CONTEXT *" parameter, which can be slow.

The analysis routine OnStackChangeIf() keeps track of some metrics on stack usage and tests whether the threshold has been reached. If the threshold is crossed, it returns non-zero, and Pin executes the DoBreakpoint() analysis routine.

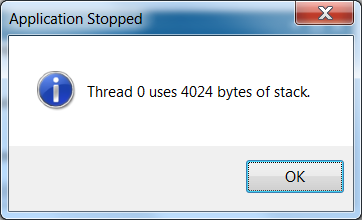

The interesting part of DoBreakpoint() is at the very end, where it calls PIN_ApplicationBreakpoint(). This API causes Pin to stop the execution of all threads and triggers a breakpoint in the debugger. There is also a string parameter to PIN_ApplicationBreakpoint(), which the debugger prints at the console when the breakpoint triggers. A Pintool can use this string to tell the user why a breakpoint triggered. In our example tool, this string says something like "Thread 10 uses 4000 bytes of stack".

Please refer to the documentation of PIN_ApplicationBreakpoint() and read the note about avoiding an infinite loop of calls to the analysis function.

We can see the breakpoint feature in action in our example tool by using the "stackbreak 4000" command like this:

Linux:

(gdb) monitor stackbreak 4000 Will break when thread uses more than 4000 bytes of stack. (gdb) c Continuing. Thread 0 uses 4000 bytes of stack. Program received signal SIGTRAP, Trace/breakpoint trap. 0x0000000000400e27 in Fibonacci (num=0) at fibonacci.cpp:34 (gdb)

When you are done, you can either continue the application and let it terminate, or you can quit from the debugger:

Linux:

(gdb) quit The program is running. Exit anyway? (y or n) y

Connecting the Debugger Later

In the previous example, we used the Pin switch -appdebug to stop the application and debug it from the first instruction. You can also enable Pin's debugging extensions without stopping at the first instruction. The following example shows how you can use the stack-debugger tool to start the application and attach with the debugger only after it triggers a stack limit breakpoint.

Linux:

$ ../../../pin -appdebug_enable -appdebug_silent -t obj-intel64/stack-debugger.so -stackbreak 4000 -- obj-intel64/fibonacci 1000

The -appdebug_enable switch tells Pin to enable application debugging without stopping at the first instruction. The -appdebug_silent switch disables the message that tells how to connect with the debugger. As we will see later, the Pintool can print a custom message instead. Finally, the "-stackbreak 4000" switch tells the stack-debugger tool to trigger a breakpoint when the stack grows to 4000 bytes. When the tool does trigger a breakpoint, it prints a message like this:

Linux:

Triggered stack-limit breakpoint. Start GDB and enter this command: target remote :45462

You can now connect with the debugger as you did before, except now the debugger stops the application at the point where the stack-debugger tool triggered the stack-limit breakpoint.

Linux:

gdb fibonacci (gdb) target remote :45462 0x0000000000400e27 in Fibonacci (num=0) at fibonacci.cpp:37 (gdb)

Let's look at the code in the tool that connects to the debugger now.

The ConnectDebugger() function is called each time the tool wants to stop at a breakpoint. It first calls PIN_GetDebugStatus() to see if Pin is already connected to a debugger. If not, it uses PIN_GetDebugConnectionInfo() to get the TCP port number that is needed to connect the debugger to Pin. This is, for example, the "45462" number that the user types in the "target remote" command. After asking the user to start the debugger, the tool then calls PIN_WaitForDebuggerToConnect() to wait for the debugger to connect. If the user doesn't start the debugger after a timeout period, the tool prints a message and then continues executing the application.

As before, you can either continue the application and let it terminate, or you can quit from the debugger:

Linux:

(gdb) quit The program is running. Exit anyway? (y or n) y

Advanced Debugging Extensions on Windows

On Windows, the advanced debugging extensions work with Microsoft Visual Studio 2012 or greater. There is no support for earlier versions of Visual Studio, so make sure you have that version installed. Also, the Express edition of Visual Studio doesn't support IDE extensions, so it will not work with the Pin debugger extensions. Therefore, you must install the Professional edition (or greater). If you are a student, you may be able to get the Professional edition for free. Check the Microsoft web site or with your school's IT department for details.

After you have installed Visual Studio, you must also install the Pin extension for Visual Studio. Look for an installer named "pinadx-vsextension-X.Y.bat" in the root of the Pin kit. Run it as administrator.

The remainder of this section assumes that you are able to build the "stack-debugger" tool, so if you want to follow along, you must have the following software installed:

- Visual Studio 2012, Professional edition (or greater).

- The Pin debugger extension for Visual Studio 2012 or greater (pinadx-vsextension-X.Y.bat).

In order to start this tutorial, you will probably want to build the example tool "stack-debugger.cpp", which is available in the directory "source\tools\ManualExamples". To do this, open a Visual Studio command shell and type the following commands. (Use "TARGET=intel64" instead, if you want to build a 64-bit version of the tool.)

C:\> cd source\tools\ManualExamples C:\> make TARGET=ia32 obj-ia32/stack-debugger.dll

After you have done this, start Visual Studio and open the sample solution file at "source\tools\ManualExamples\stack-debugger-tutorial.sln". Then build the sample application "fibonacci" by pressing F7. Make sure you can run the application natively by pressing CTRL-F5.

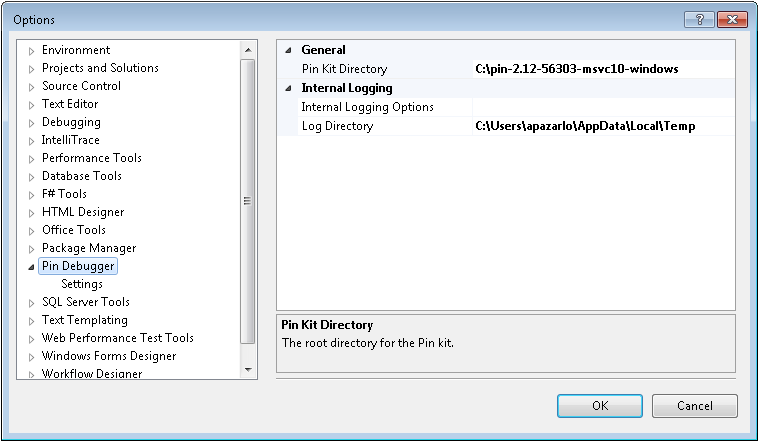

Now let's try running the "fibonacci" application under Pin with the "stack-debugger" tool. To do this, you must first set the "Pin Kit Directory" from TOOLS->Options->Pin Debugger.

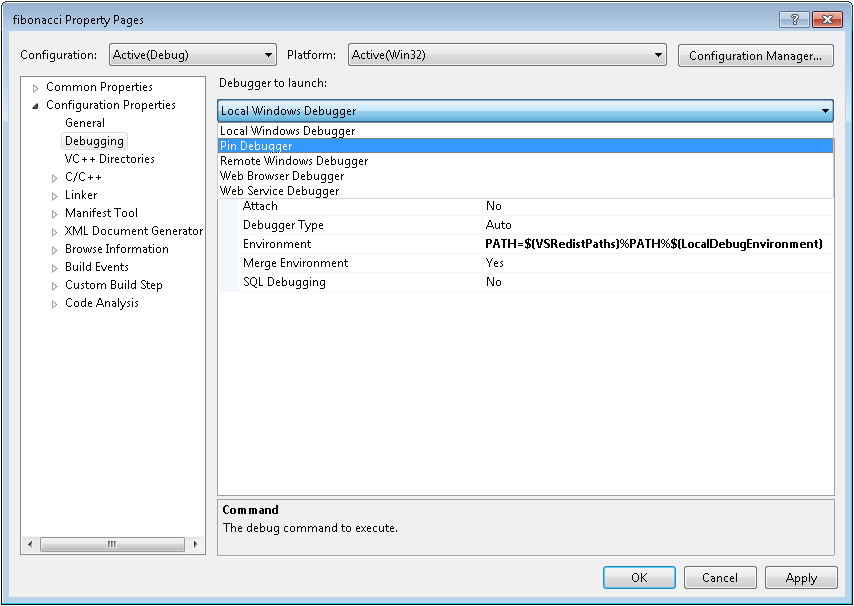

Then you have to adjust the "fibonacci" project properties in Visual Studio: right-click on the "fibonacci" project in the Solution Explorer, choose Properties, and then click on Debugging. Change the drop-down titled "Debugger to launch" to "Pin Debugger" as shown in the figure below.

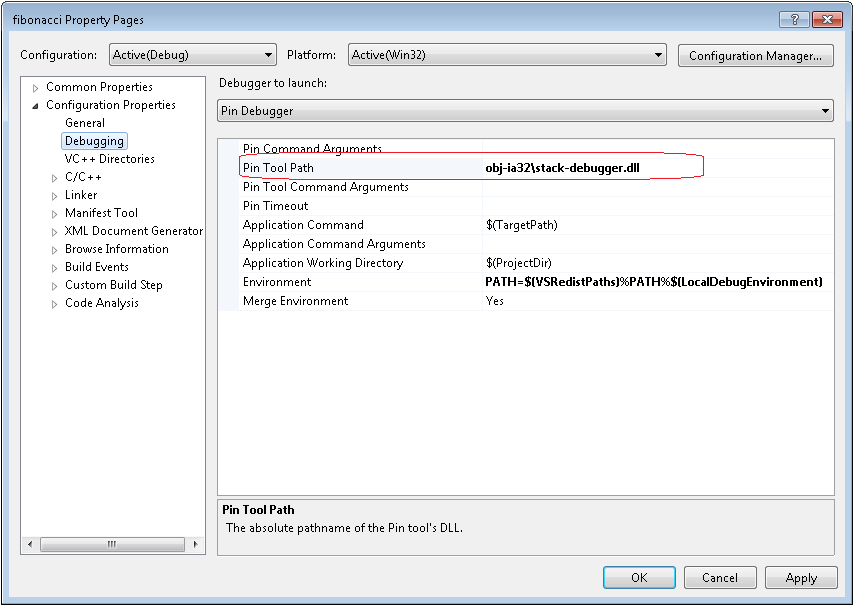

Then, set the "Pin Tool Path" property by browsing to the "stack-debugger.dll". Press OK when you are done.

Visual Studio is now configured to run the "fibonacci" application under your Pintool. However, before you continue, set a breakpoint in "main()" so that execution stops in the debugger. Then press F5 to start debugging.

You should now see a normal-looking debugger session, although your application is really running under control of Pin. All of the debugger features still work as you would expect. You can set breakpoints, continue execution, display the values of variables, and even view the disassembled code. All of the information that you observe in the debugger shows the application's "pure" state. The details of Pin and the tool's instrumentation are hidden. For example, the disassembly view shows only the application's instructions, not any of the instructions inserted by the tool. However, when you continue execution (e.g. with F5 or F10), the application executes along with your tool's instrumentation code.

Now, let's see an alternative way to debug the "fibonacci" application under Pin with the "stack-debugger" tool in Visual Studio. After you have built the "stack-debugger" tool, open a command shell and start the application with the debugging extensions enabled. This will cause Pin to stop immediately before the first instruction.

C:\> cd source\tools\ManualExamples C:\> ..\..\..\pin -appdebug -t obj-ia32\stack-debugger.dll -- debug\fibonacci.exe 1000 Application stopped until continued from debugger. Pin ready to accept debugger connection on port 30840

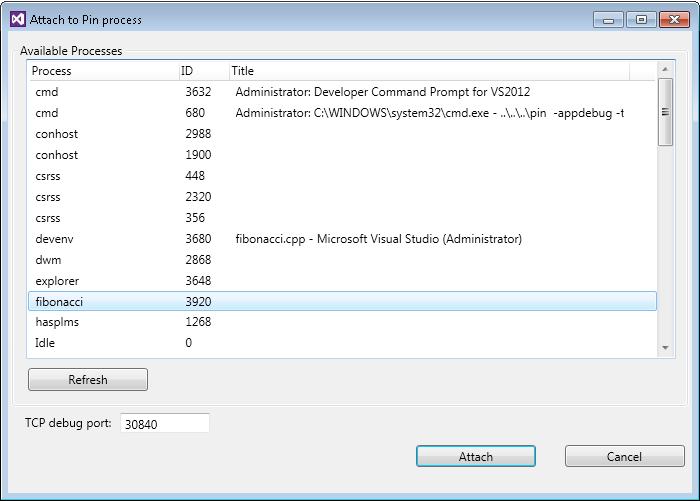

Open the source\tools\ManualExamples\fibonacci.cpp in Visual Studio and set a breakpoint to stop the execution in the debugger. To attach with Visual Studio to the process that is running under Pin, select "Attach to Pin Process" on the DEBUG menu. Select from the Available Processes table the "fibonacci" process, enter the port number that Pin printed and click Attach.

Adding New Debugger Commands

The previous section illustrated how you can enable the normal debugger features while running an application under Pin. Now, let's see how your Pintool can add new custom debugger commands, even without changing Visual Studio. Custom debugger commands are useful because they allow you to control your Pintool interactively from within a live debugger session. For example, you can ask your Pintool to print out information that it has collected, or you can interactively enable instrumentation only for certain phases of the application.

To illustrate, see the call to PIN_AddDebugInterpreter() in the stack-debugger tool. That API sets up the following call-back function:

The PIN_AddDebugInterpreter() API allows a Pintool to establish a handler for extended debugger commands. For example, the code snippet above implements the new commands "stats" and "stacktrace on". You can execute these commands in Visual Studio by opening "DEBUG->Windows->Pin Console" in the IDE.

A Pintool can do various things when the user types an extended debugger command. For example, the "stats" command prints out some information that the tool has collected. Any text that the tool writes to the "result" parameter is printed to the Visual Studio Pin Console window. Note that the CONTEXT parameter has the register state for the debugger's "focus" thread, so the tool can easily display information about this focus thread.

You can also use an extended debugger command to interactively enable or disable instrumentation in your Pintool, as demonstrated by the "stacktrace on" command. For example, if you wanted to quickly run your Pintool over the application's initial start-up phase, you could run with your Pintool's instrumentation disabled until a breakpoint is triggered. Then, you could use an extended command to enable instrumentation only during the interesting part of the application. In the stack-debugger example above, the call to PIN_RemoveInstrumentation() causes Pin to discard any previous instrumentation, so the tool re-instruments the code when the debugger continues execution of the application. As we will see later, the tool's global variable "EnableInstrumentation" adjusts the instrumentation that it inserts.

Semantic Breakpoints

The last major feature of the advanced debugging extensions is the ability to stop execution at a breakpoint by calling an API from your tool's analysis code. This may sound simple, but it is very powerful. Your Pintool can use instrumentation to look for a complex condition and then stop at a breakpoint when that condition occurs.

The "stack-debugger" tool illustrates this by using instrumentation to observe all the instructions that allocate stack space, and then it stops at a breakpoint whenever the application's stack usage reaches some threshold. In effect, this adds a new feature to the debugger that could not be practically implemented using traditional debugger technology because a traditional debugger can not reasonably find all the instructions that allocate stack space. A Pintool, however, can do this quite easily via instrumentation.

The example code below from the "stack-debugger" tool uses Pin instrumentation to identify all the instructions that allocate stack space.

The call to INS_RegWContain() tests whether an instruction modifies the stack pointer. If it does, we insert an analysis call immediately after the instruction, which checks to see if the application's stack usage exceeds a threshold.

Also notice that all the instrumentation is gated by the global flag "EnableInstrumentation", which we saw earlier in the "stacktrace on" command. Thus, the user can disable instrumentation (with "stacktrace off") in order to execute quickly through uninteresting parts of the application, and then re-enable it (with "stacktrace on") for the interesting parts.

The analysis routine OnStackChangeIf() returns TRUE if the application's stack usage has exceeded the threshold. When this happens, the tool calls the DoBreakpoint() analysis routine, which will stop at the debugger breakpoint. Notice that we use if / then instrumentation here because the call to DoBreakpoint() requires a "CONTEXT *" parameter, which can be slow.

The analysis routine OnStackChangeIf() keeps track of some metrics on stack usage and tests whether the threshold has been reached. If the threshold is crossed, it returns non-zero, and Pin executes the DoBreakpoint() analysis routine.

The interesting part of DoBreakpoint() is at the very end, where it calls PIN_ApplicationBreakpoint(). This API causes Pin to stop the execution of all threads and triggers a breakpoint in the debugger. There is also a string parameter to PIN_ApplicationBreakpoint(), which is displayed in Visual Studio when the breakpoint triggers. A Pintool can use this string to tell the user why a breakpoint triggered. In our example tool, this string says something like "Thread 10 uses 4000 bytes of stack".

We can see the breakpoint feature in action in our example tool by typing this command in the Pin Console window:

>stackbreak 4000 Will break when thread uses more than 4000 bytes of stack.

Then press F5 to continue execution. The application should stop in the debugger again with a message like this:

When you are done, you can either continue the application with F5 or terminate it with SHIFT-F5.

Applying a Pintool to an Application

An application and a tool are invoked as follows:

pin [pin-option]... -t [toolname] [tool-options]... -- [application] [application-option]..

These are a few of the Pin options are currently available. See Command Line Switches for the complete list.

- -t toolname: Specifies the Pintool to use. If you are running a 32-bit application in an IA-32 architecture, or a 64-bit application on an Intel(R) 64 architecture, only -t <toolname> is needed. If you are running an application on an Intel(R) 64 architecture, where all of the components in the chain are either 32-bit or 64-bit, but not both, only -t <toolname> is needed. If you are running an application on an Intel(R) 64 architecture, where components in the chain are both 32-bit and 64-bit, use -t64 <64-bit toolname> to specify the 64-bit tool binary followed by -t <32-bit toolname> to specify the 32-bit tool binary and the tool options. For more information, see Instrumenting Applications on Intel(R) 64 Architectures

-

-t64 toolname: Specify 64-bit tool binary for Intel(R) 64 architecture. If you are running an application on an Intel(R) 64 architecture, where components in the chain are both 32-bit and 64-bit, use -t64 together with -t as described above. See Instrumenting Applications on Intel(R) 64 Architectures.

Important: Using -t64 without -t is not recommended, since in this case when given a 32-bit application, Pin will run the application without applying any tool. - -p32 toolname: Specify Pin binary for IA-32 architecture. See Instrumenting Applications on Intel(R) 64 Architectures

- -p64 toolname: Specify Pin binary for Intel(R) 64 architecture. See Instrumenting Applications on Intel(R) 64 Architectures

- -pause_tool n: is a useful Pin-option which prints out the process id and pauses Pin for n seconds to permit attaching with gdb. See Tips for Debugging a Pintool.

- -follow_execv: Execute with Pin all processes spawned by execv class system calls.

-

-injection mode: Where mode is one of dynamic, self, child, parent. UNIX-only See Injection.

The tool-options follow immediately after the tool specification and depend on the tool used.

Everything following the – is the command line for the application.

For example, to apply the itrace example (Instruction Address Trace (Instruction Instrumentation)) to a run of the "ls" program:

../../../pin -t obj-intel64/itrace.so -- /bin/ls

To get a listing of the available command line options for Pin:

pin -help

To get a listing of the available command line options for the itrace example:

../../../pin -t obj-intel64/itrace.so -help -- /bin/ls

Note that in the last case /bin/ls is necessary on the command line but will not be executed.

Instrumenting Applications on Intel(R) 64 Architectures